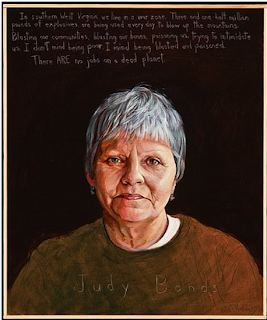

Remembering Judy Bonds

Posted on January 4, 2011 by dana

Judy was so many thing to so many people. This is part of my version of her.

“I want you to notice nature, how geese are in flight and they form a V in a leadership role…The lead goose, when he gets tired of flapping his wings, he drops to the back and the next goose comes up front. Without stopping, without fussing, without whining. He becomes that next leader, he or she, that’s what we have to do.” -Judy Bonds, PowerShift 2007

Judy Bonds passed away last night. She was a key leader in the fight against mountaintop removal coal mining, in the global fight against climate change and in the fight for environmental justice for communities across the US and the world.

She was a good friend and a hero; I love her funny jokes, her generosity, her bullheaded stubbornness, and how considerate she was. I miss Judy explaining the best way to walk down a steep mountain without stumbling, the best way to make pintos, and the best way to make a major corporate bank stop funding mountaintop removal, and Judy making us watch and re-watch a spoof version of the “All the Single Ladies” music video. She was a strategic genius, a fierce warrior, a truly brilliant thinker, and a nice, funny, loving person.

Another thing Judy was, was gorgeous, with her movie star brown eyes, and everyone declared that when the movie was made about her life, of course Sally Fields would play Judy.

Judy was dedicated to a just society; she saw the struggles for justice as interconnected. She saw straight through appearances and took people for who they were, and what they could contribute. She welcomed you, and everyone.

This summer when Judy and her family learned how sick she was, everything was full of life and green and long sunny days, and now, suddenly, cancer. Musicians came and played for Judy in the hospital, and the riot and laughter and foot stomping delighted her roommate and got everyone kicked out, except Judy of course.

I spent the rest of that day staring through tears at percentages and third stage lung cancer on the internet, the porch swing creaking back and forth, and it felt like everything in the city and the mountains all around us was hoping and hoping.

We got the call late at night, already in bed, and the news kept us pinned down to the mattress, laying lungs to lungs. I thought about our breathing, the swelling of air in our chests, and all the other people who held a piece of Judy, laying in bed with eyes wide open, thinking of her, hearing her voice.

Oxygen is something that is denied to so many people because of coal; particulates ruin lungs. The whole cycle, the coal fired power plants, the thick air where mountains are blown up for coal, the dusty hollers where coal is processed, and, of course, the lungs of those digging it out. And coal is taking our lungs and now our whole atmosphere, through climate change. I feel outrageously privileged for the ability to pull air into my lungs. And I feel outraged.

When coal takes your lungs, it begins to take your ability to yell and holler, to sigh and laugh and make jokes, but it doesn’t take your voice. When asked if she had any words to share with the thousands gathered to stand against mountaintop removal in DC this past September, Judy asked everyone to “Fight Harder.”

Sometimes people accuse activists of being against everything, instead of standing for something positive. To me, Judy was always an example what we are fighting for, what we want, what we deserve. Dignity, health, heritage and an earth to live on, the simple and sacred bonds of family.

“Your heart is a muscle the size of your fist – keep loving, keep fighting” is a quote I have seen attributed to Dalia Sapon-Shevin. In my memories of Judy, she is always doing everything with her whole heart, and she is fighting hard, yes, Judy was incredibly tough and fierce, but what made her so tough was her blazing love, and the diamond hard vision she shared with all of us, of what was worth fighting for.

Learn more about Judy and her incredible life at Coal River Mountain Watch’s website.

From: Dana Kuhnline

In Memory of Judy Bonds

Thursday, January 6, 2011

For Judy, who had the courage to "step out."

For Judy, who had the courage to "step out."

by Joyce M. Barry on Wednesday, January 5, 2011 at 10:51am

On a January evening in 2003 Coal River Mountain Watch Co-Director, Judy “Julia” Bonds was home with her grandson when the telephone rang, and the caller ID revealed the incoming call was from California. Bonds answered, and the man on the other end of the line identified himself as Richard Goldman, phoning to inform her that she was the 2003 North American recipient of the Goldman Environmental prize for her work against mountaintop removal coal mining in Appalachia. Bonds, who knew nothing about the Goldman foundation or this prestigious prize that annually gives monetary awards to one environmental justice activist from each continent, casually responded, ‘Oh, okay. Well thanks. I appreciate that.’

During their brief conversation Goldman gave Bonds a web address, and encouraged her to read more about this prize. She explains, “I looked it up on the computer and then I was in total shock…it took my breath away.” Bonds learned that she was one of 7 environmental justice activists in the world that year to win $125,000 for her work with the Coal River Mountain Watch. She says winning this prize was personally monumental but also significant for her organization and the anti-MTR movement, as “People began to realize who CRMW was. They began to realize what MTR is and it started a snowball effect” with more people becoming educated about MTR and its impact on Appalachian communities, and joining the fight to end it.

Five years earlier, in 1998, Judy Bonds, entered the CRMW offices seeking help after being forced off her land in Marfork Hollow, near Whitesville, WV by coal operations that rendered the area unfit for habitation. Bonds, whose family has lived in this area for 10 generations, noticed dramatic changes in her environment when Massey coal operations began there in the 1990’s. She witnessed color and consistency changes to the water sources in her backyard, and when her grandson alerted her to fish kills in the water, she knew something was horribly wrong. After this Bonds says, “I started to notice as my neighbors moved out, there was coal trucks running constantly and it just …devalued our property, our quality of life. We were in danger…and it was basically the quality of the air and water that made me find out more about what’s happening in my own holler, and the coal industry.” Feeling under siege from MTR blasting, the persistent presence of coal trucks, the inability to drink water in her home, or visit the family cemetery, she moved 9 miles away to Rock Creek, West Virginia. She was the last resident to leave the community of Marfork.

Prior to joining the CRMW, Bonds had no experience in grassroots activist politics, but from an early age, she developed a deep sensitivity to economic and social injustice. All the men in her family, including her father, grandfather, ex-husband, cousins and others worked in nearby coal mines. She spent her childhood in Birch Creek, the upper reaches of Marfork hollow, where her family grew large gardens, foraged for edible plants in the surrounding mountains, kept livestock, and hunted animals for their subsistence. Bonds lived in Birch hollow until she was 7, when a coal company forced her family off their land. They settled nearby in Marfork hollow, and her father worked for Bethlehem Coal Company.

She recalls seeing one of her father’s paychecks, and the anger she felt upon learning his weekly compensation was a meager $15. She said “fifteen dollars for a man risking his life and his health. $15 dollars is what he gets for that?” Even though Bonds had no political activist experience before joining the CRMW, she credits her mother with imparting a strong sense of justice in her: “she was a very strong willed, opinionated woman. I remember listening to my mother rant and rave about Buffalo Creek …And I remember hearing my mother talk a little bit about Mother Jones, and John L. Lewis and about Matewan…so, a little bit of that outrage against injustices was instilled in me at an early age.” In the anti-MTR movement, Bonds has a reputation for speaking bluntly, motivated by an angry passion that is unpalatable to some people, particularly coal industry supporters. However, she is unapologetic saying, ‘that’s who I am. I can’t apologize for that. I lost my diplomacy a long time ago.’ She, like other grassroots activists in the movement, has been the victim of threats and intimidation for speaking out against coalfield injustices, but remains unwavering in her position.

Arguably, Judy Bonds, along with Larry Gibson, Maria Gunnoe, Ed Wiley and Lorelei Scarbro are some of the most prominent faces of the anti-MTR movement in West Virginia. They are West Virginia natives, with deep historical ties to the Appalachian region. They, along with the other people profiled in this book, have felt the negative impacts of Big Coal firsthand. They also refuse to remain silent while this industry obliterates their communities. Bonds, in particular, takes a firm stand on the issue and believes other people should as well. She argues, “if you do not raise your finger to stop an injustice, you’re the same as that person doing the injustice.” She has been called a “folk celebrity” for her work with the CRMW, a coalfield Erin Brockovich. However, Bonds is quick to say that she is just one of many, “a reflection,” of Big Coal’s impact on Southern West Virginia, and of the numerous people taking stands against the coal industry in this age of mountaintop removal coal mining. She says “I’m just the first one out there because there’s a lot more women that have deeper and bigger and more compelling stories to tell …that’s what makes it so good is that the rest of these women are now telling their stories because one woman had the courage to step out.”

For Judy, who had the courage to "step out."

Wednesday, January 5, 2011

Mark Schmerling remembers Judy

Hi,

This Mark Schmerling, a photographer who has made many trips to southern West Virginia to document the horrors created by the coal industry and perpetuated by our corrupt government.

I met Judy in September, 2006, at the Coal River Mountain Watch office in Whitesville, and made a few photos there, before Judy had to be someplace else important. After that day, I was fortunate enough to spend at least a bit of time with Judy on a few occasions. My initial impression of her indomitable spirit, her inspirational presence, and above all, her immense love for her fellow human beings, remains firmly intact.

Attached are a few photos. The black and white of Judy was taken in front of the CRMW office in September, 2006. The three color photos were all taken May 8, 2007, when Judy was one of the eloquent members of the Coalfield Delegation to the United Nations Commission on Sustainability, in New York City. In two of these photos, Judy and her companions are listening to some of the music from the anti-mountaintop removal concert held that evening. In the other, she is speaking at an anti-MTR press conference earlier that day.

Judy's actions and her memory inspire me to keep making photographs that tell the real story of coal, the people affected by the industry, and those brave individuals, like Judy, who fight for justice, simply because it's the right thing.

When I looked through my camera lens at Judy's face, I was drawn deep beyond her toughness and her iron will, into her beautiful eyes, and these eyes spoke love for her fellow highlanders, and for all humanity.

Peace and justice.

Mark Schmerling

This Mark Schmerling, a photographer who has made many trips to southern West Virginia to document the horrors created by the coal industry and perpetuated by our corrupt government.

| Judy as seen by Mark Schmerling |

Attached are a few photos. The black and white of Judy was taken in front of the CRMW office in September, 2006. The three color photos were all taken May 8, 2007, when Judy was one of the eloquent members of the Coalfield Delegation to the United Nations Commission on Sustainability, in New York City. In two of these photos, Judy and her companions are listening to some of the music from the anti-mountaintop removal concert held that evening. In the other, she is speaking at an anti-MTR press conference earlier that day.

Judy's actions and her memory inspire me to keep making photographs that tell the real story of coal, the people affected by the industry, and those brave individuals, like Judy, who fight for justice, simply because it's the right thing.

When I looked through my camera lens at Judy's face, I was drawn deep beyond her toughness and her iron will, into her beautiful eyes, and these eyes spoke love for her fellow highlanders, and for all humanity.

Peace and justice.

Mark Schmerling

Coalminer’s Daughter Turned Activist Wins Top Enviro Prize

Coalminer’s Daughter Turned Activist Wins Top Enviro Prize

From an article dated 04/18/03

Living on EarthCURWOOD: The Goldman Prize is often called the Nobel for the environment. Each year, activists on each continent receive the award worth $125,000 for their work. The winner this year for North America is Judy Bonds, the West Virginia woman working to stop the coal mining method called mountaintop removal. Jeff Young of West Virginia Public Broadcasting has this profile of a coal miner's daughter fighting to end a coal mining practice.

YOUNG: A former post office in Whitesville, West Virginia is home to the grassroots group, Coal River Mountain Watch. It might as well be home for the group's director, Judy Bonds. Most of her waking hours are spent here organizing protests, lobbying lawmakers, and writing to editors and senators to stop mountaintop removal. The 51-year-old Bonds points to a wall-sized map of Southern West Virginia. It shows the contours of the state's coal country.

BONDS: I can tell you exactly where they're heading by looking at a topomap, a USGS map. These coal companies want the cheap, easy, quick, fast way, regardless of human concern. And what we're looking at is the prize, called Pond Knob.

YOUNG: Bonds thinks Pond Knob on Coal River Mountain could be the next ridge flattened by mountaintop removal. The mining blasts the tops from hills to expose coal. Tons of leftover rock and dirt are dumped into valleys, burying hundreds of miles of Appalachia's headwater streams. The mining has so altered the landscape that the map Bonds pours over is no longer accurate, but she still scans for tiny signs of hope, like the crosses marking small family cemeteries.

BONDS: There's a law in West Virginia, and they cannot mine within 300 feet of a cemetery. They have to give some sort of protection to that cemetery. Basically, I would say our dead ancestors are helping us to fight these coal companies, and are another way to put a chair against the door to keep the wolf out. We're backed in the corner. We're using any means we can to save our lives.

YOUNG: Bonds knows the mining is changing more than the land. It's changing the people who live on it. It's certainly changed her.

[SOUND OF CAR STARTING]

YOUNG: Just six years ago, Bonds was waiting tables at Pizza Hut. She lived quietly in one of the sharp, narrow valleys people here call "hollows." Marfork Hollow was her family's home for six generations. Now, Marfork is the name of a coal company, and Bonds is just another visitor driving by.

BONDS: Every time I pass by this hollow, I look, and it hurts. It breaks my heart, because this is where I was born and raised.

YOUNG: Bonds remembers when Massey Energy Company's Marfork mine opened ten years ago. It brought truck traffic, dust, and the noise of blasting. The extent of the damage became clear the day the stream near her house turned black with coal waste.

BONDS: And I heard my grandson say "Mawmaw." And I looked at him and he said, "What's wrong with these fish?" And he had both his little hands full of fish, dead fish. And I looked around him and there were dead fish laying all over the stream. And that was a slap in the face.

YOUNG: Bonds eventually sold her family land and moved about 10 miles south. She watched as more acres were mined and more coal wastes blackened streams. She didn't know what she could do about it until she attended a rally against mountaintop removal and realized she was not alone.

[FOLK MUSIC PLAYING]

YOUNG: Former West Virginia congressman turned activist, Ken Hechler, performed that day six years ago. Bonds joined the group Coal River Mountain Watch, and Hechler watched her go quickly from a bystander to a leader.

HECHLER: There are several things about Judy that developed as her activism developed. First of all, she's a person of great determination and great courage and great dedication. And secondly, she's a person who inspires confidence among people that she helps to organize.

YOUNG: In 1999, Hechler and Bonds organized a march to commemorate the Battle of Blair Mountain, an historic moment in the early effort to unionize the state's coal miners. Hechler says he knew Bonds had grit when the small group of marchers was surrounded by angry counter-demonstrators.

HECHLER: We were attacked by a group of toughs. And I looked over and I saw Judy Bonds, and she had a look of great determination on her face. I started out being scared, and then terrified, but I got inspired by her courage.

YOUNG: Many of those counter-demonstrators were coal miners. Bonds realized she needed to reach out to miners who saw her work as a threat to theirs. The United Mine Workers of America fights many of the things conservationists want, including restrictions on mountaintop removal. But union representative Mike Caputo says he was able to work with Bonds' group on some issues.

CAPUTO: The bridge was built by Judy when we sat down and chatted with her, and spoke quite frankly that there's going to be issues that were probably going to be at odds on them, maybe might even be fighting each other at one time or another. But we've seen some common ground there, and we've seen that there are many, many issues that we can join hands on. And Judy helped develop that relationship.

YOUNG: Bonds and Caputo fought for better regulation of overweight coal trucks, and the union helped her point out the poor environmental record at many non-union mines. Bonds is proud of the headway she's made with the union and with state regulators. But it's hard to point to solid victories. Coalfield residents twice won major court cases limiting mountaintop removal, only to have both rulings overturned. And the Bush administration is changing federal rules to allow mines to dump rock and dirt in streams.

But if Bonds grows discouraged, she returns to the stream at Marfork Hollow to remind herself what she's working for.

BONDS: The celebration of life was everyday, the connection everyday to the community and to the land, and to the rivers and the streams. And that's basically what we're trying to preserve. This is innocence. That's what we're trying to preserve, the innocence, the innocence of a time left behind, of a connection to community, and to people, and to heritage, and culture, and to the environment. It's a tradition that goes on.

[SOUNDS OF TRUCKS]

YOUNG: A rumbling truck brings her back to the present, and a coal company security guard approaches.

SECURITY GUARD: Can I help you?

BONDS: I was just here looking at where I used to live at. I just come up to look. I haven't been here for a while.

SECURITY GUARD: The only thing we ask now is you get hazard trained, because this is coal company property...

YOUNG: Bonds asks the guard if he heard spring peepers sing this year, or the hoot owl that roosted in the walnut tree her father planted. Soon the two are talking about wildflowers and black bears. Judy Bonds is back to work in her own subtle way, building bridges wherever she can.

For Living On Earth, I'm Jeff Young, in Marfork Hollow, West Virginia.

Related link:

The 2003 Goldman Environmental Prize

From an article dated 04/18/03

Living on EarthCURWOOD: The Goldman Prize is often called the Nobel for the environment. Each year, activists on each continent receive the award worth $125,000 for their work. The winner this year for North America is Judy Bonds, the West Virginia woman working to stop the coal mining method called mountaintop removal. Jeff Young of West Virginia Public Broadcasting has this profile of a coal miner's daughter fighting to end a coal mining practice.

YOUNG: A former post office in Whitesville, West Virginia is home to the grassroots group, Coal River Mountain Watch. It might as well be home for the group's director, Judy Bonds. Most of her waking hours are spent here organizing protests, lobbying lawmakers, and writing to editors and senators to stop mountaintop removal. The 51-year-old Bonds points to a wall-sized map of Southern West Virginia. It shows the contours of the state's coal country.

BONDS: I can tell you exactly where they're heading by looking at a topomap, a USGS map. These coal companies want the cheap, easy, quick, fast way, regardless of human concern. And what we're looking at is the prize, called Pond Knob.

YOUNG: Bonds thinks Pond Knob on Coal River Mountain could be the next ridge flattened by mountaintop removal. The mining blasts the tops from hills to expose coal. Tons of leftover rock and dirt are dumped into valleys, burying hundreds of miles of Appalachia's headwater streams. The mining has so altered the landscape that the map Bonds pours over is no longer accurate, but she still scans for tiny signs of hope, like the crosses marking small family cemeteries.

BONDS: There's a law in West Virginia, and they cannot mine within 300 feet of a cemetery. They have to give some sort of protection to that cemetery. Basically, I would say our dead ancestors are helping us to fight these coal companies, and are another way to put a chair against the door to keep the wolf out. We're backed in the corner. We're using any means we can to save our lives.

YOUNG: Bonds knows the mining is changing more than the land. It's changing the people who live on it. It's certainly changed her.

|

Judy Bonds delivering a speech in Washington, D.C. 2002 calling for the end to mountaintop removal. (Photo: Deana Steiner Smith) |

YOUNG: Just six years ago, Bonds was waiting tables at Pizza Hut. She lived quietly in one of the sharp, narrow valleys people here call "hollows." Marfork Hollow was her family's home for six generations. Now, Marfork is the name of a coal company, and Bonds is just another visitor driving by.

BONDS: Every time I pass by this hollow, I look, and it hurts. It breaks my heart, because this is where I was born and raised.

YOUNG: Bonds remembers when Massey Energy Company's Marfork mine opened ten years ago. It brought truck traffic, dust, and the noise of blasting. The extent of the damage became clear the day the stream near her house turned black with coal waste.

BONDS: And I heard my grandson say "Mawmaw." And I looked at him and he said, "What's wrong with these fish?" And he had both his little hands full of fish, dead fish. And I looked around him and there were dead fish laying all over the stream. And that was a slap in the face.

YOUNG: Bonds eventually sold her family land and moved about 10 miles south. She watched as more acres were mined and more coal wastes blackened streams. She didn't know what she could do about it until she attended a rally against mountaintop removal and realized she was not alone.

[FOLK MUSIC PLAYING]

YOUNG: Former West Virginia congressman turned activist, Ken Hechler, performed that day six years ago. Bonds joined the group Coal River Mountain Watch, and Hechler watched her go quickly from a bystander to a leader.

HECHLER: There are several things about Judy that developed as her activism developed. First of all, she's a person of great determination and great courage and great dedication. And secondly, she's a person who inspires confidence among people that she helps to organize.

YOUNG: In 1999, Hechler and Bonds organized a march to commemorate the Battle of Blair Mountain, an historic moment in the early effort to unionize the state's coal miners. Hechler says he knew Bonds had grit when the small group of marchers was surrounded by angry counter-demonstrators.

|

| Judy Bonds (center) at a protest against mountaintop removal at the West Virginia State Capitol in 2002. (Photo: Vivian Stockman, OVEC) |

HECHLER: We were attacked by a group of toughs. And I looked over and I saw Judy Bonds, and she had a look of great determination on her face. I started out being scared, and then terrified, but I got inspired by her courage.

YOUNG: Many of those counter-demonstrators were coal miners. Bonds realized she needed to reach out to miners who saw her work as a threat to theirs. The United Mine Workers of America fights many of the things conservationists want, including restrictions on mountaintop removal. But union representative Mike Caputo says he was able to work with Bonds' group on some issues.

CAPUTO: The bridge was built by Judy when we sat down and chatted with her, and spoke quite frankly that there's going to be issues that were probably going to be at odds on them, maybe might even be fighting each other at one time or another. But we've seen some common ground there, and we've seen that there are many, many issues that we can join hands on. And Judy helped develop that relationship.

YOUNG: Bonds and Caputo fought for better regulation of overweight coal trucks, and the union helped her point out the poor environmental record at many non-union mines. Bonds is proud of the headway she's made with the union and with state regulators. But it's hard to point to solid victories. Coalfield residents twice won major court cases limiting mountaintop removal, only to have both rulings overturned. And the Bush administration is changing federal rules to allow mines to dump rock and dirt in streams.

But if Bonds grows discouraged, she returns to the stream at Marfork Hollow to remind herself what she's working for.

BONDS: The celebration of life was everyday, the connection everyday to the community and to the land, and to the rivers and the streams. And that's basically what we're trying to preserve. This is innocence. That's what we're trying to preserve, the innocence, the innocence of a time left behind, of a connection to community, and to people, and to heritage, and culture, and to the environment. It's a tradition that goes on.

[SOUNDS OF TRUCKS]

YOUNG: A rumbling truck brings her back to the present, and a coal company security guard approaches.

SECURITY GUARD: Can I help you?

BONDS: I was just here looking at where I used to live at. I just come up to look. I haven't been here for a while.

SECURITY GUARD: The only thing we ask now is you get hazard trained, because this is coal company property...

YOUNG: Bonds asks the guard if he heard spring peepers sing this year, or the hoot owl that roosted in the walnut tree her father planted. Soon the two are talking about wildflowers and black bears. Judy Bonds is back to work in her own subtle way, building bridges wherever she can.

For Living On Earth, I'm Jeff Young, in Marfork Hollow, West Virginia.

Related link:

The 2003 Goldman Environmental Prize

John,

Thank you for putting together a place for people to share and read about Judy.

I wrote this up after looking back at an interview I did

I'd be honored if you include it in the on line memorial.

Thanks

Jeff Young

In April, 2003, I spent the day with Judy, interviewing her for a profile for the public radio program Living on Earth. She had just won the prestigious Goldman Prize for her work with Coal River Mountain Watch.

We got in her car (leased, she said--she changed cars often so those who wished her harm wouldn’t see her coming) and went to see her old homestead land on Marfork Hollow.

“Every time I pass by this hollow, I look, and it hurts. It breaks my heart, because this is where I was born and raised.”

She parked and we walked around. Her family lived there six generations but it’s Massey’s land now. She showed me a walnut tree her father, a coal miner, had planted. She showed me the stream where she and later her grandchildren used to splash and play, back before it ran black with mine waste.

“The celebration of life was everyday, the connection everyday to the community and to the land, and to the rivers and the streams. This is innocence. And that's basically what we're trying to preserve, a connection to community, and to people, and to heritage, and culture, and to the environment.”

Pretty soon a security guard came along. He was polite, but the message was clear: leave. We drove to her group’s Whitesville office to look over a topo map of the region, the boundaries of pending mountaintop removal permits drawn on it. Judy’s green eyes scanned for the little crosses that indicate old family cemeteries, which might win a few hundred feet of buffer from the mining.

“They have to give some sort of protection to that cemetery,” she said. “Our dead ancestors are helping us to fight these coal companies, and are another way to put a chair against the door to keep the wolf out.”

Thank you for putting together a place for people to share and read about Judy.

I wrote this up after looking back at an interview I did

I'd be honored if you include it in the on line memorial.

Thanks

Jeff Young

In April, 2003, I spent the day with Judy, interviewing her for a profile for the public radio program Living on Earth. She had just won the prestigious Goldman Prize for her work with Coal River Mountain Watch.

We got in her car (leased, she said--she changed cars often so those who wished her harm wouldn’t see her coming) and went to see her old homestead land on Marfork Hollow.

“Every time I pass by this hollow, I look, and it hurts. It breaks my heart, because this is where I was born and raised.”

She parked and we walked around. Her family lived there six generations but it’s Massey’s land now. She showed me a walnut tree her father, a coal miner, had planted. She showed me the stream where she and later her grandchildren used to splash and play, back before it ran black with mine waste.

“The celebration of life was everyday, the connection everyday to the community and to the land, and to the rivers and the streams. This is innocence. And that's basically what we're trying to preserve, a connection to community, and to people, and to heritage, and culture, and to the environment.”

Pretty soon a security guard came along. He was polite, but the message was clear: leave. We drove to her group’s Whitesville office to look over a topo map of the region, the boundaries of pending mountaintop removal permits drawn on it. Judy’s green eyes scanned for the little crosses that indicate old family cemeteries, which might win a few hundred feet of buffer from the mining.

“They have to give some sort of protection to that cemetery,” she said. “Our dead ancestors are helping us to fight these coal companies, and are another way to put a chair against the door to keep the wolf out.”

Thousands Pay Tribute to Judy Bonds:

Tuesday, January 4, 2011

Thousands Pay Tribute to Judy Bonds:

Thousands Pay Tribute to Judy Bonds: She Has Been to the Mountaintop--and We Must Fight Harder to Save ItShe was a tireless, funny, and inspiring orator, and a savvy and brilliant community organizer. She was fearless in the face of threats. As the godmother of the anti-mountaintop removal movement, she gave birth to a new generation of clean energy and human rights activists across the nation. In a year of mining disasters and climate change set backs, she challenged activists to redouble their efforts.

As one of the great visionaries to emerge out of the coalfields, Julia "Judy" Bonds reminded the nation that her beloved Appalachians had been to the mountaintop--and in her passing last night, thousands of anti-mountaintop removal mining and New Power activists from around the country are reminding the Obama administration and the country's environmental justice movement of Bonds' powerful legacy and parting words to "don't let up, fight harder and finish off" the outlaw ranks of Big Coal and end the egregious crime of mountaintop removal.

In a special email message last night, Coal River Mountain Watch director Vernon Haltom announced the passing of Bonds, the Goldman Prize winner and Executive Director of Coal River Mountain Watch. Bonds, 58, had battled advanced stage cancer over the past several months. "One of Judy's last acts was to go on a speaking trip, even though she was not feeling well, shortly before her diagnosis," Haltom wrote. "I believe, as others do, that Judy's years in Marfork holler, where she remained in her ancestral home as long as she could, subjected her to Massey Energy's airborne toxic dust and led to the cancer that wasted no time in taking its toll. Judy will be missed by all in this movement, as an icon, a leader, an inspiration, and a friend."

Here's a clip from a special tribute to Judy by On Coal River filmmakers Adams Wood and Francine Cavanaugh:

Judy Bonds from On Coal River on Vimeo.

A little more than a decade ago, sitting on the coal dust-swept front porch with her grandson--the ninth generation of their family to reside in Marfork Hollow in West Virginia--Bonds was outraged to hear her 7-year-old grandson describe an escape route should a nearby massive coal waste dam break and flood their valley. "I knew in my heart there was really no escape," Bonds told an interviewer in 2003. "How do you tell a child that his life is a sacrifice for corporate greed? You can't tell him that, you don't tell him that, but of course he understands that now."

Forced by an encroaching strip mine to move from her family's ancestral land, Bonds spent the next decade as a full-time crusader (and coal miner's daughter) to bring her grandson's message of central Appalachia's role as a national sacrifice zone from the devastating impact of mountaintop removal strip mining to millions of Americans across the country.

For fellow activist Bo Webb, who went to jail and organized side-by-side with Bonds for years in the Coal River Valley, Judy was one of the better angels of our nature: "Judy was one of God's most loyal and dedicated Angels in the battle of good vs. evil. I will miss her, we will all miss her. After much suffering, she now stands before God, without doubt holding a very special place in His heart. May God bless and comfort those that love and adore Judy. May God bless and comfort her wonderful family, and may God give us the unity and conviction to fight on in her honor and His name."

"Judy Bonds was our Hillbilly Moses," added Bob Kincaid, president of the Coal River Mountain Watch board. "She knew better than anyone that we WILL make it to the Promised Land: out of the poisonous bondage of coal companies. She will not cross over with us on that great day, but her spirit will join us, and inform the freedom that sings from our hearts. Mother Jones, meet Judy. Judy, Mother."

In a special Living on Earth radio interview with Jeff Young in 2003, Bonds recalled her grandson holding a handul of dead fish contaminated by coal waste. "And I looked around him and there were dead fish laying all over the stream. And that was a slap in the face."

From the United Nation to the halls of Congress, and at universities and conferences from Maine to California, Bonds testified to the ravages of strip mining on her community's waterways, economy and culture. Her riveting speeches galvanized activists from the hollers to the urban neighborhoods, and among national environmental organizations.

"Judy was a strong, powerful voice that always sang wisdom, inspiration, passion and determination to my soul," wrote Chris Hill, the National Field Organizer for the Hip Hop Caucus in Washington, DC. "She was a voice that will forever speak volumes to the reasons why I fight for justice from the mountains to the inner cities."

"Judy often remarked how she proudly stood shoulder to shoulder with outside groups like Rainforest Action Network," added Scott Parkin, Senior Campaigner for RAN's Coal Campaign. "During an E.P.A. action last March, I saw her beaming with a big smile and much excitement as we worked together to make mountaintop removal a national issue and take the fight to end it out of the hills and hollers of Appalachia into offices of the power-holders in Washington D.C."

"She inspired thousands in the movement to end mountaintop removal and was a driving force in making it what it has become," Haltom wrote in his email message to national activists. "I can't count the number of times someone told me they got involved because they heard Judy speak, either at their university, at a rally, or in a documentary. Judy endured much personal suffering for her leadership. While people of lesser courage would candy-coat their words or simply shut up and sit down, Judy called it as she saw it. She endured physical assault, verbal abuse, and death threats because she stood up for justice for her community."

"One of the happiest days of my life was when we announced the funding for a new school to replace Marsh Fork Elementary," said filmmaker and activist Jerry Cope, who worked with Coal River Valley residents to move a school imperiled by coal dust and a dangerous coal slurry impoundment. "Without Judy's inspiration, I would have never become involved and she will forever be a source of inspiration to me."

In a special tribute to Judy by filmmakers Jordan Freeman and Mari-Lynn Evans, Judy asked for the right to go home. "I miss my home," she pleaded. "I want to go home."

Like generations before her, Judy Bonds has finally gone home to her Marfolk Holler.

And thousands of coalfield residents, activists and leaders will continue the battle to ensure that Coal River Mountain--the last mountain--remains in her view, and mountaintop removal is abolished once and for all.

Julia 'Judy' Bond, 58, dies; outspoken foe of mountaintop strip mining

Wednesday, January 5, 2011

Julia 'Judy' Bond, 58, dies; outspoken foe of mountaintop strip mining

By Emma Brown

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, January 4, 2011; 11:28 PM

Judy, front and center in a DC blizzard, STOP MTR (JLW)

Julia "Judy" Bonds, the spitfire daughter of a West Virginia coal miner who worked as a Pizza Hut waitress before she became, in midlife, a leading voice of the grass-roots resistance to mountaintop strip mining, died Jan. 3 of cancer at a hospital in Charleston, W.Va. She was 58.

Ms. Bonds was one of the most visible and outspoken activists against what is sometimes called "mountaintop removal," a mining practice peculiar to Appalachia in which peaks are sheared off with explosives to expose the coal seams below.

A coalfields native who scraped by working in restaurants and convenience stores, Ms. Bonds was equivocal about the risks of mining until the 1990s, when the A.T. Massey Coal Co. arrived in Marfork hollow, one of the narrow, green valleys that wind through the Appalachian Mountains in southern West Virginia.

Ms. Bonds lived most of her life in that hollow, as did generations of her family before her. In childhood, she had come to know its fishing spots and swimming holes; later, as a young single mother, she had raised her daughter in Marfork.

"There is nothing like being in the hollows," she once told the Los Angeles Times. "You feel snuggled. You feel safe. It seems like God has his arms around you."

But when Massey Energy Co., as it is now known, began blasting, the air became filled with dust and cacophony, and families began moving out. Ms. Bonds refused to go. Marfork was home.

Then her 6-year-old grandson - who, like other children in the hollow, had developed a case of asthma that couldn't be ignored - asked her a question: "What's wrong with these fish?"

He was standing in the local creek, holding fistfuls of dead fish, with more floating belly-up around his ankles.

"I knew something was very, very wrong," Ms. Bonds told Sierra magazine. "So I began to open my eyes and pay attention."

She discovered that Marfork was one of many West Virginia hollows dealing with the effects of mountaintop mining, which was developed in the 1970s but whose use began accelerating about two decades ago.

And she learned that Massey had planned a dam farther up Marfork hollow - an impoundment that would hold millions of gallons of coal sludge. Her family would be in danger if the dam failed, and such dams had failed before - including in 1972 at Buffalo Creek, W.Va., where 125 people were killed in the toxic flood.

When she heard her grandson concocting escape plans in the event of a dam break, Ms. Bonds - the last holdout in Marfork - knew that it was time to move and time to call attention to the threats of mountaintop mining to clean air, clean water and the Appalachian way of life.

She became a volunteer with and then executive director of Coal River Mountain Watch, a local grass-roots group. She taught herself how to challenge the mining companies' federal and state permit applications.

Embracing her hillbilly identity, she shrugged off the argument that rural people needed the coal industry's jobs.

"If coal is so good for us hillbillies," she said at a 2008 Appalachian Studies Association conference, "then why are we so poor?"

photo by JLW

Massey - the subject of scrutiny after an explosion at its underground Upper Big Branch Mine killed 29 West Virginia miners in April - was a frequent target of Ms. Bonds's. She confronted coal industry executives, organized marches, lobbied at the West Virginia statehouse and in Washington and traveled the country talking to young people.

Her message was consistent: The health and safety of Appalachia's poor were being sacrificed for the profits of energy companies.

"We're a colony here, and the coal companies rule," the writer Michael Shnayerson quotes her as saying in his 2008 book, "Coal River." "We can complain all we want, but those complaints are just swept aside in the name of progress and jobs. It's like we're selling our children's feet to buy shoes."

She stood her ground despite insults and threats from neighbors and coal workers, who felt their livelihoods were threatened by her forthrightness and her rage. At a protest against Massey last year, a woman clad in an orange-striped miner's shirt slapped Ms. Bonds while other Massey supporters cheered in approval.

"Judy always insisted that the story of coal and mountaintop removal was a human story, a human rights story," said Mary Anne Hitt, director of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign and a longtime ally of Ms. Bonds's. "She personified that story at great personal risk."

Ms. Bonds was earning $12,000 a year at her job as an activist when, in 2003, she was awarded the prestigious $125,000 Goldman Environmental Prize. After paying for her grandson's braces, helping her daughter buy a car and paying off the family's mortgage, Ms. Bonds donated nearly $50,000 to Coal River Mountain Watch - an amount equal to the organization's annual budget.

Once little known outside the coalfields, mountaintop removal has in recent years become the subject of environmental and public health controversy with a national profile.

A plotline in one of the most celebrated novels of 2010, Jonathan Franzen's "Freedom," tells the story of a hardscrabble West Virginia community uprooted by a mountaintop removal project. Last October, more than 100 people were arrested at the White House during a protest against mountaintop removal.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, between 1985 and 2001, debris scraped from hundreds of thousands of acres choked more than 700 miles of streams. Under President Obama, the EPA has sought to restrict new permits for the practice and tighten safeguards for natural resources

Such recognition of the problems related to mountaintop removal is "due in no small part," Hitt said, "to the leadership and the sacrifice of Judy Bonds."

Julia Belle Thompson was born Aug. 27, 1952, at the family home in the Birch Hollow part of what is now called Marfork. When Ms. Bonds was growing up, the place was better known as Packsville, said Ms. Bond's daughter, Lisa Henderson.

Ms. Bonds was one of eight children, two of whom died at birth. Her father retired from working in underground coal mines at 65 and died several months later of pneumoconiosis, better known as black lung disease.

Besides her daughter, of Rock Creek, W. Va., survivors include a brother, three sisters and a grandson.

"See that? That's the ironweed," Ms. Bonds once said, pointing out a purple-flowered plant to a visiting reporter. "They say they're a symbol for Appalachian women. They're pretty. And their roots run deep. It's hard to move them."

We love you Judy (JLW

Julia 'Judy' Bond, 58, dies; outspoken foe of mountaintop strip mining

By Emma Brown

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, January 4, 2011; 11:28 PM

Judy, front and center in a DC blizzard, STOP MTR (JLW)

Julia "Judy" Bonds, the spitfire daughter of a West Virginia coal miner who worked as a Pizza Hut waitress before she became, in midlife, a leading voice of the grass-roots resistance to mountaintop strip mining, died Jan. 3 of cancer at a hospital in Charleston, W.Va. She was 58.

Ms. Bonds was one of the most visible and outspoken activists against what is sometimes called "mountaintop removal," a mining practice peculiar to Appalachia in which peaks are sheared off with explosives to expose the coal seams below.

A coalfields native who scraped by working in restaurants and convenience stores, Ms. Bonds was equivocal about the risks of mining until the 1990s, when the A.T. Massey Coal Co. arrived in Marfork hollow, one of the narrow, green valleys that wind through the Appalachian Mountains in southern West Virginia.

Ms. Bonds lived most of her life in that hollow, as did generations of her family before her. In childhood, she had come to know its fishing spots and swimming holes; later, as a young single mother, she had raised her daughter in Marfork.

"There is nothing like being in the hollows," she once told the Los Angeles Times. "You feel snuggled. You feel safe. It seems like God has his arms around you."

But when Massey Energy Co., as it is now known, began blasting, the air became filled with dust and cacophony, and families began moving out. Ms. Bonds refused to go. Marfork was home.

Then her 6-year-old grandson - who, like other children in the hollow, had developed a case of asthma that couldn't be ignored - asked her a question: "What's wrong with these fish?"

He was standing in the local creek, holding fistfuls of dead fish, with more floating belly-up around his ankles.

"I knew something was very, very wrong," Ms. Bonds told Sierra magazine. "So I began to open my eyes and pay attention."

She discovered that Marfork was one of many West Virginia hollows dealing with the effects of mountaintop mining, which was developed in the 1970s but whose use began accelerating about two decades ago.

And she learned that Massey had planned a dam farther up Marfork hollow - an impoundment that would hold millions of gallons of coal sludge. Her family would be in danger if the dam failed, and such dams had failed before - including in 1972 at Buffalo Creek, W.Va., where 125 people were killed in the toxic flood.

When she heard her grandson concocting escape plans in the event of a dam break, Ms. Bonds - the last holdout in Marfork - knew that it was time to move and time to call attention to the threats of mountaintop mining to clean air, clean water and the Appalachian way of life.

She became a volunteer with and then executive director of Coal River Mountain Watch, a local grass-roots group. She taught herself how to challenge the mining companies' federal and state permit applications.

Embracing her hillbilly identity, she shrugged off the argument that rural people needed the coal industry's jobs.

"If coal is so good for us hillbillies," she said at a 2008 Appalachian Studies Association conference, "then why are we so poor?"

photo by JLW

Massey - the subject of scrutiny after an explosion at its underground Upper Big Branch Mine killed 29 West Virginia miners in April - was a frequent target of Ms. Bonds's. She confronted coal industry executives, organized marches, lobbied at the West Virginia statehouse and in Washington and traveled the country talking to young people.

Her message was consistent: The health and safety of Appalachia's poor were being sacrificed for the profits of energy companies.

"We're a colony here, and the coal companies rule," the writer Michael Shnayerson quotes her as saying in his 2008 book, "Coal River." "We can complain all we want, but those complaints are just swept aside in the name of progress and jobs. It's like we're selling our children's feet to buy shoes."

She stood her ground despite insults and threats from neighbors and coal workers, who felt their livelihoods were threatened by her forthrightness and her rage. At a protest against Massey last year, a woman clad in an orange-striped miner's shirt slapped Ms. Bonds while other Massey supporters cheered in approval.

"Judy always insisted that the story of coal and mountaintop removal was a human story, a human rights story," said Mary Anne Hitt, director of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign and a longtime ally of Ms. Bonds's. "She personified that story at great personal risk."

Ms. Bonds was earning $12,000 a year at her job as an activist when, in 2003, she was awarded the prestigious $125,000 Goldman Environmental Prize. After paying for her grandson's braces, helping her daughter buy a car and paying off the family's mortgage, Ms. Bonds donated nearly $50,000 to Coal River Mountain Watch - an amount equal to the organization's annual budget.

Once little known outside the coalfields, mountaintop removal has in recent years become the subject of environmental and public health controversy with a national profile.

A plotline in one of the most celebrated novels of 2010, Jonathan Franzen's "Freedom," tells the story of a hardscrabble West Virginia community uprooted by a mountaintop removal project. Last October, more than 100 people were arrested at the White House during a protest against mountaintop removal.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, between 1985 and 2001, debris scraped from hundreds of thousands of acres choked more than 700 miles of streams. Under President Obama, the EPA has sought to restrict new permits for the practice and tighten safeguards for natural resources

Such recognition of the problems related to mountaintop removal is "due in no small part," Hitt said, "to the leadership and the sacrifice of Judy Bonds."

Julia Belle Thompson was born Aug. 27, 1952, at the family home in the Birch Hollow part of what is now called Marfork. When Ms. Bonds was growing up, the place was better known as Packsville, said Ms. Bond's daughter, Lisa Henderson.

Ms. Bonds was one of eight children, two of whom died at birth. Her father retired from working in underground coal mines at 65 and died several months later of pneumoconiosis, better known as black lung disease.

Besides her daughter, of Rock Creek, W. Va., survivors include a brother, three sisters and a grandson.

"See that? That's the ironweed," Ms. Bonds once said, pointing out a purple-flowered plant to a visiting reporter. "They say they're a symbol for Appalachian women. They're pretty. And their roots run deep. It's hard to move them."

We love you Judy (JLW

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)